by Paola Rosà

A definition to be analysed

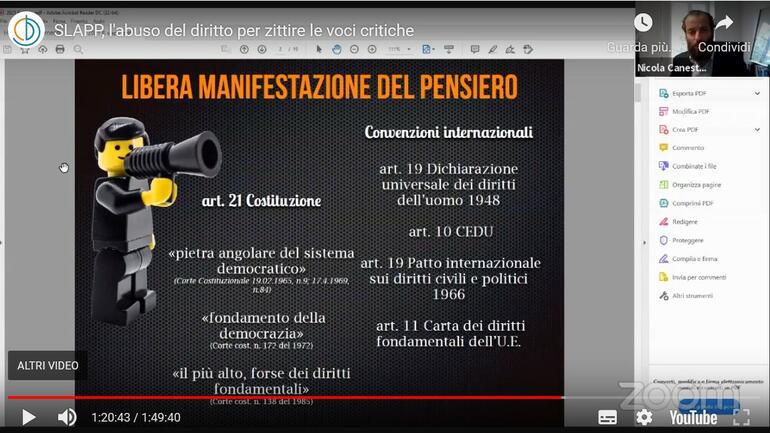

SLAPPs, strategic lawsuits against public participation, are well known to be a threat to democracy (study commissioned by the EU Commission), a weapon in the hands of the powerful (Greenpeace ), an abuse of the legal system (Coalition Against Slapps in Europe ), a tool to intimidate and silence dissenting voices (Nicola Canestrini , lawyer), and a democratic emergency (Chamber of Italian Journalists).

This screenshot is taken from a webinar hosted by OBCT on 28 June 2021, and it is part of the presentation given by Nicola Canestrini, criminal lawyer: it presents the main legislative and legal sources of freedom of speech, including the Italian Constitution, international conventions and charters, and definitions given in some decisions of the Constitutional Court. Freedom of speech is cited as “maybe the highest of fundamental rights” and “cornerstone of the democratic system”.

In spite of its importance and gravity, the SLAPP phenomenon is still unknown to most citizens, and the abuse of lawsuits and civil claims for damages seems to be far from being seen as a real issue or as a concrete threat to democracy. Maybe because the “academic” definition and the approach of NGOs, human rights group, and journalists unions, still seem to affect restricted categories of citizens who have to cope with a limited category of cases: the issue is worrying, very worrying for journalists, human rights defenders, and activists, but it seems to leave the rest of the population indifferent, untouched, unfazed. This perception gap needs to be filled.

The Italian media landscape is rich in examples.

The strong polarisation of society helps create a permanent conflict where even journalists and activists are seen as fighters belonging to one side, and not as defenders of the right to be informed.

Journalists can be regarded as “troublemakers” (“this label is often used in newsrooms to define colleagues that have been sued for their investigations, they told us that these troublemakers are putting the outlet in danger”, personal declaration to the author) and this label is misused to gain public condemnation.

The announcement of a lawsuit to silence a journalist – instead of being seen as a shameful move, as it is in Sweden, for example - is paradoxically seen as a legitimate move to silence criticism. The confrontation shifts from the level of freedom of speech to the courtroom, and public reaction is too often weak.

In this video Raffaele Lorusso, General Secretary of the FNSI, the Italian Journalists Union, explains that since the beginning of October 2021 Italian journalists are in a state of labour unrest, protesting against the Italian government and the Italian parliament. Among the reasons, the lack of political will to tackle the problem of SLAPPS.

There is the need to fill this perception gap, and to stress the importance of watchdogs for the entire community, well beyond political positioning and beliefs. Hence the importance of training, dissemination, research, and monitoring as well as support for the victims.

Two words can be helpful in finding the direction, in order to improve knowledge and raise awareness, i.e. strategy and public participation.

What is a strategy?

On the one hand, there is the need to distinguish a legitimate legal action put forward to defend one's reputation from a strategy that clearly has the aim to silence criticism and intimidate future critics.

The strategy of the SLAPPer can be clearly identified looking at the frequency (how many times do they sue the same person or outlet or organisation for the same topic?), at the numbers of victims (how many critics do they sue?), at the amounts claimed (how many hundreds of thousands of Euros do they claim?): strategic SLAPPers are far from seeking to defend their reputation, they aim at destroying the enemy, at intimidating all attempts to criticise and investigate. Intimidate one to silence many.

What is public participation?

On the other hand, there is the need to find a commonly accepted definition of public participation, in relation to information as common good to be protected. In fact, the real victim of most SLAPP cases is information: while the sued journalist is busy defending themselves, while the activists are listening to their lawyers' recommendations and waiting for the next hearing, and even if they are acquitted in the end, there is THE victim of SLAPP, which is information. During that time of silence, while defendants are intimidated and busy with legal issues, all the investigations and information they were managing for the public interest are left behind. And this suspension of the citizens' right to be informed should be quantified, and there should be a way to punish this suspension.

Many examples can be mentioned. The pesticide trial in Italy is certainly a very clear one: during the preliminary phases of the trial against the abuse of pesticides in South Tyrol, very few media mentioned the abuse of pesticides in South Tyrol. The defamation lawsuit against the Umweltinstitut Muenchen and the Austrian filmmaker Alexander Schiebel could certainly scare all other media in the region, and only the strong reaction of the victims and their lawyer made sure to open the discussion and raise awareness.

Disparity of power and the abuse of the mechanisms

The case of the airport and the city councillors in Florence.

A lawsuit can be used as a threat and the disparity of power among the players is of course very important. As the case of the Florence Airport confirms, the conflict is publicly admitted: the contenders simply use any weapon available, thus abusing the legal system and misusing the pitfalls of any system to delay, suspend, prolong, and postpone the end of the conflict.

In Florence, some local politicians are publicly criticising the management of Toscana Aeroporti (managing the Florence Airport), they have been doing so in many official meetings of the city council, and of course on their personal social media pages. At the beginning of January 2022, Toscana Aeroporti sued two city councillors, one regional councillor, and the spokesperson of an association for defamation; the public prosecutor asked to dismiss the lawsuit, recognising the “right to freedom of expression and to political action”. This means that even the public prosecutor has not seen a single reason to go on with the lawsuit, the crime is not to be seen. But Toscana Aeroporti opposed this decision and a hearing in front of the judge is to take place by the end of January 2022. In spite of everything, the fight must go on.

This case is one of the many cases proving that the system suffers too many attempts at misuse, abuse, and forced interpretation. There is the need to find internal defence mechanisms to prevent these abuses.

Time is money

In all cases analysed by OBCT, time is key. In SLAPP cases, victims cannot say that “time is on my side”. In places where the rule of law suffers from lengthy trials and a high number of litigations (like Italy, but also Croatia and Serbia), time is on the SLAPPers' side. Cases where public participation is at stake, where information as a public good risks to be silenced, should be dismissed at an early stage.

Nello Trocchia published an investigation about Pegaso (an online university) in 2014, and only in December 2021 was the claim for damages rejected by a court in Naples: for all those years, Nello Trocchia lived with the Damocles sword of 38 million Euros to be paid as damages to reputation. In the end, all went well for him and for his investigation. But what happened in the meantime?

In a webinar hosted by OBCT and Articolo 21 on 10 January, Nello Trocchia stressed the side effects of that claim for damages: “I was quite lucky, as the claim also involved the editor and the publisher of the magazine I worked for; so, I was not alone, as L'Espresso has a very strong legal team. We also need to help victims face this issue: if we leave them alone, there will be a desert in the next future, and there won't be anyone left to tell what is happening in some areas, there won't be voices to report about organised crime and corruption”.

The risk of self-censorship

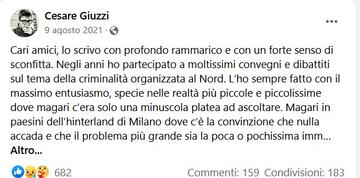

The story of Cesare Giuzzi can be taken as a perfect example: the reporter for the daily newspaper Corriere della Sera announced through Facebook that he would give up all public events, because he was tired of losing time and energy defending himself from abusive lawsuits filed for what he had said during these meetings with students and citizens.

His words give an excellent picture of what it means to deal with SLAPPs as a victim.

Here is a partial translation of his post published on 9 August 2021: it contains a complete definition of SLAPP given by an investigative journalist, a direct and detailed description of side effects, consequences, and collateral damages caused by abusive lawsuits.

Posted by Cesare Giuzzi, journalist of Corriere della Sera, 9 August 2021

Dear friends, I'm writing this with the deepest regret and with a strong sense of defeat. In the last years I have participated in meetings and debates on organised crime in Northern Italy. I have always done it with the highest enthusiasm, especially in the smallest towns and villages, even if there were very few people to listen to me. It was for example in little villages around Milan, where there is the strong belief that nothing happens, and that the biggest issue is the high or law rate of immigration. But these rural areas are the preferred and invisible thriving site of the most important 'ndrangheta families in Lombardia.

I have always participated without asking for a fee, and as I have never written books about it, people did not have to buy my book either. And my enthusiasm grew when I was in front of a younger audience, during the Summer camps of the anti-mafia association Libera, and with the young researchers of the University course about organised crime of the State University of Milan led by Nando Dalla Chiesa. I'm not a professor nor an expert, I'm just a reporter writing crime news, and I have a passion for genealogical trees, old documents, and brand new bar receipts.

Every time I was invited – I don't keep track of the invitations, but I guess we are close to 100 meetings – I participated with enthusiasm, with gratitude.

I am not an expert nor a professor, I have always tried to apply the journalistic method to these meetings, telling what it won't be reported in big newspapers: who is behind that bar in the village square, or behind that company that made business with the garbage boss, who is that local politician who often meets members of organised crime. It was a kind of local narrative, about our neighbours, about mafia in Northern Italy.

But now, unluckily, I have to stop.

In the last few years, beside the lawsuits that I receive for the articles I write for Corriere della Sera (and God always bless the skills, the professionalism, and the endless patience of lawyer Malavenda), I have also started to receive lawsuits for what I said in meetings and debates. Sometimes, people were in the room, some other times, they received videos and recordings from someone sitting there. Being those public events, I know it's part of the game.

I usually participate being a journalist but as a private citizen, so, I personally cover the legal expenses. Not everybody knows it, but if you are sued, if you receive a meritless lawsuits – as 99.9 per cent of the cases end with a dismissal as there is no base for a defamation case – the plaintiff has the possibility to oppose to the dismissal. It means that, even if the prosecutor doesn't see the crime and asks the judge to dismiss the lawsuit, you as a defendant have to hire a lawyer to assist you during the dismissal hearing: these hearings end in 99999.99% of cases with a dismissal. But in order to have that, you'll have to have paid a lawyer, to have prepared a defence paper, and produce thousands of pages of legal documents and evidence, to defend what you have written or said, and obviously to have paid for all this.

I have always considered this rule a bit weird.

In practice, it means that there will be a policeman or a carabiniere who will come in search for you, to identify you, to let you sign the appointment of a lawyer, to notify you copy of the call at court. Well, now, I'm so used to the procedure, that they, the policemen, know me very well, they don't even visit me but they call me and ask me to pop in, so, I go to the police station and they don't have to come to my place. In the beginning, the doorkeeper thought I was like Pablo Escobar, as he used to see policemen and carabinieri coming to search for me almost every week.

Originally, I was sued only for what I wrote in the newspaper, and I am lucky that Corriere della Sera has a good legal defence. Now, I am sued for what I say in public, for what I say during interviews on tv. In my life, like many other colleagues, I have been sued more than 50 times, by mafia men, crime groups and individuals, killers, robbers, corrupt politicians, non-corrupt politicians, public administrators, relatives of mafia men, policemen, carabinieri, businessmen, bar owners, by the parents of a boy who committed suicide. Once, for one single article about the Swiss companies belonging to the Papalia, I have been sued 6 times by 6 different people: the boss, his wife, his daughter, his son-in-law, his figurehead...

I agree that the right to sue is a legitimate one. But so far, no judge has ever decided against me in all my cases. Anyway, when you win, you are not reimbursed for the unjust allegations that you suffered. You were right. And that's it.

But now I'm tired, I'm fed up. That's why I need a break. I can't spend my days writing statements of defence, trace documents and pieces of evidence and facts, and on top of that only hope that things will go well. Because, in the end, every hearing in front of the judge is open to any result, even if you think you have all the chances to win.

There is the plaintiff, there is the judge, there is the lawyer, but in the end you are the defendant. And if things go wrong, you'll have to face a trial. It is not that I feel personally stalked, it's a general problem in Italy: a journalist can be sued even if he/she tells the truth. The plaintiff doesn't risk anything. They try, they pay a lawyer, that's it.

I think that self-censorship is the worst thing for a journalist. But that's the only thing I can do now. I couldn't participate in an event without telling everything I know; journalists must be precise, and tell what they know, if they know it's true.

That's why I prefer to stop. I hope you can understand.

In private, I'll be always available, for a document to be found in my archives, for a dialogue, for anything. But the rest has to stop, unluckily.

This content is part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries. The project is co-funded by the European Commission.