Written by Claudia Pierobon and Paola Rosà and presented at the expert talk on anti-SLAPP solutions held in Brussels on November 12th 2019

Thirty years after the publication of the first academic definition of SLAPP in the United States, politicians, academics, and stakeholders are starting to address the issue in Europe too, although the problem on the field (a strategic lawsuit aimed at silencing dissent) has been harassing journalists and activists for years. Politicians and big companies, in Italy too, can afford expensive lawyers: they usually file a criminal defamation lawsuit or a civil claim for damages, and wait. Simply wait. While activists and journalists are under pressure.

SLAPPs in Italy: a “democratic emergency”

The Italian media environment is gradually deteriorating due to a series of issues that are tightly intertwined. The economic crisis, legislation, and political developments have generated a hostile climate towards the press.

Reporters Sans Frontières ranked Italy 43rd in the 2019 World Press Freedom Index, as the level of violence and threats against reporters is alarming and keeps growing. According to the report of a joint fact-finding mission where OBCT participated together with ECPMF and Ossigeno per l'Informazione, around twenty Italian journalists are under police protection because of serious threats or murder attempts by the mafia or extremist groups.

Italy also registered the sharpest increase in the number of media freedom alerts in 2018, according to a report by the Council of Europe Platform for the protection of journalism and the safety of journalists.

Among all problems journalists face on the job, the Italian Communications Regulatory Authority has identified the abuse of lawsuits as the main tool to sabotage freedom of the press.

The so-called querele temerarie, frivolous and meritless defamation lawsuits, are recognised as a “democratic emergency”. As stated by Carlo Verna, President of the Italian Chamber of Journalists, they are an objective restraint to the right to inform and to be informed.

The Italian legislative framework

As the protection of the reputation of individuals may clash with freedom of expression, it is necessary to constantly balance opposite stances.

The exercise of the right to news reporting (diritto di cronaca) and of freedom of the press is granted by Art. 21 of the Constitution, and represents a cause of justification (Art. 51 Criminal Code) that makes the act of communicating information damaging the honour, the dignity, or the reputation of another person non punishable.

A landmark judgment of the Court of Cassation (October 18th, 1984) set out three criteria for the application of Art. 51:

- the social utility or social relevance of the information;

- the truthfulness of the information (which may be presumed if the journalist has seriously verified their sources);

- restraint (“continenza”), referring to the civilised form of expression, which must not “violate the minimum dignity to which any human being is entitled”.

Defamation is still a criminal offence that is punished by the Criminal Code and the Press Law. Journalists may face imprisonment up to six years and a fine (up to 50,000 Euros), even though the European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly warned Italy of the potential chilling effect caused by the mere existence of prison sentences for defamation, which constitutes a disproportionate interference with the right to freedom of expression (e.g., in Belpietro v. Italy and Ricci v. Italy).

Furthermore, according to the Press Law, in case of defamation the editors/deputy editor and publisher or the printer (for non-periodical press) can be liable in civil and criminal terms for the failure to conduct supervision of the content of the publication.

To sum up, a vexatious lawsuit is a perfectly legal action that can be undertaken both before civil and criminal courts: it can be filed as criminal proceeding for defamation or as a civil claim for compensation for damages.

Civil claims vs. criminal lawsuits

The Italian Civil Procedure Code entails several procedural advantages that make civil lawsuits even more threatening than criminal ones. In fact, in civil procedure:

- there is no preliminary scrutiny by the judicial authority (and that means longer and more expensive proceedings, while criminal proceedings are most times dismissed even before the trial);

- there is no limit to damage compensation (while in criminal procedure it is around 50,000 Euros - but also in this case it has been considered excessive and disproportionate );

- there is a much longer limitation period for filing an action (5 years against only 3 months in criminal procedure). However, it should also be considered that the crime is time-barred in 6 years, and according to Art. 2947 par. 3 Civil Code, the same prescription period applies for the civil action.

Therefore, the legislator is working on the Civil Procedure Code to introduce more effective legal instruments, as the existing ones - such as punitive damages and mandatory mediation - are not enough.

A difficult approach with numbers

Even though SLAPPs have been defined as a “democratic emergency”, it is difficult to quantify the phenomenon.

The main reason lies in the fact that data of civil claims and criminal lawsuits are recorded differently.

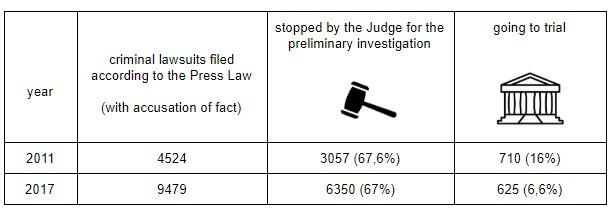

In fact, for the criminal system, the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) database registers lawsuits on the basis of the criminal offence (see the table below).

Conversely, in the civil sphere, lawsuits are recorded according to the civil action: therefore, an in-depth analysis of every single civil file for damages compensation would be necessary, as it is impossible to understand which ones are directly or indirectly linked to defamation and journalism.

Furthermore, statistics do not consider the extensive number of out-of-court settlement of disputes and self-censorships acts.

However, it is worth mentioning that around 70% of criminal cases are dismissed even before the trial thanks to the preliminary scrutiny by the judicial authority (Judge for the preliminary investigation, GIP).

Taking into consideration the extensive out-of-court settlement of disputes, the chilling effect causing self-censorship cases and the lack of provisions that could effectively discourage plaintiffs from starting SLAPPs, it is easy to suppose that this is an even wider and more serious problem.

According to the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), in 2017 there were 9,479 criminal defamation complaints that were “defined” by the Judge for the preliminary investigation (GIP): 67% of them were dismissed.

Compared to 2011, defamation complaints had doubled.

The Italian paradox

Looking at the international landscape, defamation is a crime in most countries, for instance in three-quarters of OSCE participating States. Nevertheless, many international media freedom and human rights organisations advocate for “the full decriminalization of defamation and the fair consideration of such cases in dispute-resolution bodies or civil courts”.

It needs to be stressed that the decriminalisation of defamation and the abolishment of detention penalties for defamation are to be regarded as two different requests, even if they are often mixed and confused. In fact, if defamation is decriminalised – that is if the offence is no longer a crime and is no longer in the Criminal Code, with a contextual modification of the Press Law 47/48 – the Italian system would no longer provide the guarantee of a judge’s filter and all damage claims would last for years as happens nowadays.

It is a different matter to ask for the abolishment of prison as a punishment: in this case, defamation would remain a crime (and the system would provide the guarantee of a judge’s filter), but would be punished with a financial penalty instead of imprisonment.

In Italy, in 2016, around 287 people were convicted in a final judgement regarding defamation: among them, 38 were sentenced to imprisonment, while 234 to a fine.

In 2017, there was a further increase in the number of people convicted by final judgement (from 287 to 435): 64 were sentenced to imprisonment and 336 to a fine. According to some reports, the overall rate of convictions is really low (less than 10%).

So far, legislation amendments proposed in Italy do not include decriminalisation; from any political area, legislators seem to want defamation to remain a crime, but to punish it with financial penalties and no longer with imprisonment. Nobody has ever proposed a total decriminalisation of defamation, probably because the filtering role of a judge’s evaluation in the pre-trial phase is actually considered an essential guarantee, though this can indeed seem a paradox, if compared to the international landscape and the common law countries.

Factors fostering the chilling effect

As the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association has underlined , certain legal and socio-economic frameworks could provide fertile ground for the proliferation of these reckless lawsuits.

For what concerns the Italian system, there are several factors that impact on the journalistic environment.

First, a high level of job insecurity precludes the financial capability to react to these lawsuits: usually, journalists are precarious or freelance, and most times, when they are targeted by a SLAPP, they are left alone and cannot count on the support of the publisher, especially at the local level.

Moreover, the simple threat of lengthy and costly legal procedures has a strong chilling effect on press freedom, leading to self-censorship and discouraging journalists from doing their job.

In Italy, the chilling effect of these lawsuits is increased by the excessive length of trials, criticised and condemned many times by the European Court of Human Rights.

In fact, on average, preliminary inquiries in defamation cases can take two and a half years, and it takes courts nearly four years to issue a first-degree sentence (without considering the possibility of an appeal, that would further extend the length of judicial proceedings).

Another element that fosters the chilling effect is that it is extremely easy to file a lawsuit, and since there are no limits to damage compensation, fines could be excessively disproportionate.

The state of the art in the Italian Parliament

In 2013 there was an attempt to reform the defamation law. The bill aimed to bring Italian defamation law more in line with international and European standards, including by abolishing the possibility of imprisonment for this offence. However, even though there was a general agreement in the Senate, the proposal was not approved by the Chamber of Deputies by the end of the term.

Currently, in the Italian Parliament there are 4 draft bills containing measures to deter strategic lawsuits: 2 are in the waiting list in the Chamber of Deputies (1 initiated by the Democratic Party, 1 by the 5-Star-Movement), 2 are being discussed in the Senate (1 by Forza Italia, 1 by the 5-Star Movement). 3 of them also contain other proposals to amend media laws (concerning changes to: the editor’s responsibility, the right to have a prompt correction of the news item, the creation of a new judging authority, compensation damages, fines instead of prison for the crime of defamation).

The bills differ in many aspects, but they have one thing in common, namely the cancellation of prison as a punishment for defamation.

Concerning anti-SLAPP provisions, the bills differ in the amount of the sum to be paid by the plaintiff in case of a meritless lawsuit; the Democratic Party’s bill proposes it as a fine, not as a compensation to the defendant.

Bill No. 416, signed by the deputy Walter Verini and other members of the Democratic Party, aims at re-proposing Bill No. 1119-B which was discussed, but not finally approved, in the previous parliamentary term (2013-2018). Bill No. 416 was presented in Parliament on March 27th 2018, when Verini stressed the importance of finding “a balance between the protection of one’s dignity and the right to freedom of the press”. About the “delicate” topic of meritless lawsuits, which “can become intimidation tools able to influence investigations and the free circulation of information”, Verini explains the introduction of a form of “aggravated civil responsibility”: when the plaintiffs clearly act in gross negligence or fraud, beside having to pay all expenses and a compensation to the defendant, they have to pay a fine ranging between 5% and 10% of the claimed damage. In any case, this sum shall not be higher than 30,000 Euros. This would apply to damages to reputation in general, not only to those caused by means of the press.

Bill No. 812, signed by Senator Giacomo Caliendo (member of Forza Italia and former Undersecretary of Justice in a Berlusconi government), presented on September 20th 2018, aims in many aspects to strengthen the right to one’s reputation, introducing for example a fine when a media outlet does not publish a prompt correction of false news, and increasing the fine for defamation, which remains a crime although no longer punished with imprisonment. Concerning anti-SLAPP measures, the changes to Article No. 96 of the Civil Procedure Code simply include the possibility of a compensation to be paid to the defendant, to be determined “on an equitable basis”. No sum range is provided. Bill No. 812’s provisions would apply only to damages through the press. This Bill was stopped by a vote in the Justice Commission on December 17th 2019.

The most severe measures to deter SLAPPs are contained in the draft bills proposed by members of the 5-Star Movement, both in the Chamber of Deputies and in the Senate.

Bill No. 1700, signed by Mirella Liuzzi and Francesca Businarolo, President of the Justice Commission, is the most recent one and was presented on March 26th 2019; the introductory notes are very clear in highlighting the awkwardness of the Italian situation, so different for example from the one in the USA. “In the USA, journalists have to check [...] that what they write is true. In Italy, instead, journalists have to experience a real living death (in the original: via crucis) among civil and criminal lawsuits. In Italy you can be condemned even if you tell the truth, it is enough that you use too harsh words, or secret news, or public but not publishable information”. But plaintiffs, people who sue journalists with a civil lawsuit, “don’t risk anything: they can claim a million dollar damage, and if the judge dismisses their claim, they don’t have to pay anything”. In order to make them pay something, this bill introduces Art. 97-bis in the Civil Procedure Code as a form of “responsibility”, providing for the compensation of half of the claimed damage if the dismissal is a “total” rejection. This would apply to all damage claims, not only to those made through the press.

The amount of the compensation is instead flexible, but still is calculated to be no less than a quarter of the claimed damage, according to Bill No. 835 proposed by Senator Primo Di Nicola, who worked as a journalist for decades. His proposal is very short and limited to adding a subsection to Article No. 96 of the Civil Procedure Code, adding a sort of punitive damagee: accordingly, if it is proved that the plaintiff acted in bad faith or in gross negligence, in rejecting the claim the judge would condemn the plaintiff to pay, beside the expenses, a compensation to the defendant, and this sum cannot be less than a quarter of the damages originally claimed. This provision would only concern claims for damages to the reputation made through the press.

This bill seems to be considered particularly important nowadays since it has been prioritised in the parliamentary agenda: the above mentioned bill proposed by Liuzzi-Businarolo has been “frozen” in order to have a speedy discussion of Di Nicola’s proposal. In particular, the element of novelty brought by this draft is the fixed parameter for the judge to decide the amount of the compensation: the higher the claim, the higher the fine. This proportionality principle is regarded as the main deterrent for strategic lawsuits, since they are dangerous for freedom of expression not only because they are meritless, but also because they are disproportionate in their damage claims. No merit, a lot of money: the worst combination for the greatest chilling effect on journalists.

Pros and cons

- The amount of the penalty. The application of a fine can be questionable under the constitutional viewpoint: some analysts argue that the existence of this kind of penalty can be seen as a limitation to the free exercise of constitutionally granted rights, for example under Art. 24 of the Italian Constitution which grants anyone the right to bring cases before a court of law in order to protect their rights. In fact, the first draft of the Bill foresaw a compensation of at least "half of the claimed damage": for more than a year, this version of the proposal was stuck in Parliament, till on December 17th 2019 it was amended (half became 25%) and approved by the Justice Commission of the Senate.

- The violation of equality. The creation of an ad hoc provision for journalists would conflict with the constitutionally granted right of equality before the law, as confirmed for example by Undersecretary of Justice Vittorio Ferraresi: according to him, Di Nicola’s Bill “applying to a particular category of citizens - i.e. the journalists - could violate the principle of equality stated in the Constitution”.

- The risk of changing rules. According to these views, the already existing provisions of Art. 96 of the Civil Procedure Code would be enough to deter strategic damage claims. Any increase in the amount of the fine, besides being possibly unconstitutional, would lead to unexpected consequences in other fields of application (for example, for employees claiming damages after being fired).

- The need to find new ways. The existing legal frame would not allow the implementation of an effective deterrent against SLAPPs: according to some views, the Italian system should take inspiration from the UK Defamation Law, which takes all claims to an extra-judicial field. Only here, high fines could stop strategic lawsuits. If so, however, there would be the need to appoint a system of arbitration with new rules and new procedures.

Self-defence and counter-attack

Considering that strategic lawsuits are seen by journalists as “a democratic emergency” and that legislative attempts to deter them have either been fruitless in their application or have been aborted within Parliament, journalists have developed several “emergency solutions” to defend themselves:

- as explained by Antonella Napoli, a journalist under police protection, the best way to help colleagues under threat or sued by a SLAPP is to provide them with a “media bodyguard” - in order not to let them feel alone, colleagues can re-publish their investigations and follow up on their findings;

- as decided in May 2019 by the National Council of the Chamber of Journalists , there is the commitment to implement any tool to support journalists targeted by SLAPPs;

- in 2011, the union Associazione Stampa Romana opened the helpdesk “Roberto Morrione querele temerarie”, where pro-bono lawyers assist sued journalists and since 2015 Ossigeno has been offering pro bono legal assistance to journalists and bloggers facing legal charges or suits;

- a legal tool to react and counter-attack (but only in case of a criminal trial) is the damage claim in answer to a meritless lawsuit - according to article 427 of the Criminal Procedure Code, when defendants are declared innocent, they can claim the reimbursement of expenses and also the payment of damages in case of gross negligence by the plaintiff. According to some associations, it is “a very powerful deterrent”, but it only applies to criminal lawsuits.