A special dossier curated by Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa for the Resource Centre on Press and Media Freedom

Last updated on July 25, 2019

What is hate speech?

Although the expression has become very common, there is no set definition of hate speech. In fact, the quest for a shared definition clashes with juridical, political-philosophical, and cultural debates over the boundaries of freedom of expression. How can we define – and, therefore, contrast – hate speech without limiting a fundamental freedom? Such a dilemma predates the Internet, but has been strongly revived by the digital revolution.

The different definitions of hate speech share a common ground in the documents produced by international institutions after the Second World War. According to a recommendation by the Council of Europe in 1997 , hate speech includes “all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance, including intolerance expressed by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility towards minorities, migrants and people of immigrant origin”.

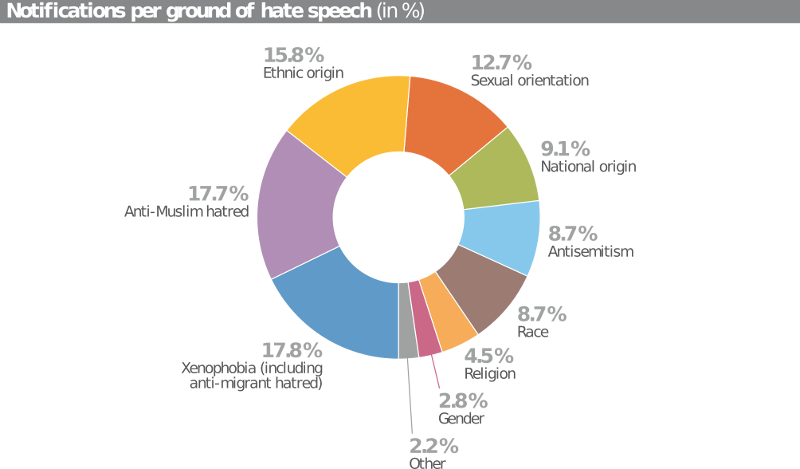

Although the expression “hate speech” gained ground during the 1990s, the observation of the phenomenon and the commitment to contrast it are not new (previously, the expression “incitement to hatred ” was preferred). For many decades, the focus was on racial hatred, antisemitism, and historical revisionism. With the new millennium, awareness on the topic has come to include religious minorities (especially Muslims, increasingly targeted by threats and discrimination) and, more recently, women, LGBT persons, the disabled, and the elderly.

In synthesis, no matter the form (written or oral, verbal or non verbal, explicit or implicit) and juridical status (possible “hate crimes”), hate speech includes any expression of violence and discrimination against other persons or groups. As hate speech targets people on the basis of their personal characteristics and/or conditions, contrasting actions need to be appropriate for the current social, economic, political, and technological context.

Efforts to contrast hate speech today face the dilemmas and contradictions of the digital age. In a recent report, the Council of Europe addressed hate speech within the wider issue of information disorder, a global tampering of contents where hate speech and so-called fake news cross paths: in this view, disinformation stems from the encounter between mis-information (spreading news that are false, but harmless) and mal-information (spreading authentic news, with the intent to harm).

Is hate speech on the rise?

Although the debate on incitement to hatred has a long history, the attention paid to hate speech has undoubtedly grown over the last years, following increasing occurrences in the digital space. As observed in this graph (that shows the occurrence of the term in the English-language publications indexed in Google Books), the expression has become common only over the last 30 years, while most initiatives by authorities and civil society are even more recent.

The lack of a shared definition of hate speech makes data gathering at the European level scarce, or uneven at best. Only over the last few years have bodies like OSCE or the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights started pressing to at least systematise national data gathering on hate crime (only partially overlapping with hate speech): since 2016, OSCE has collected statistics and compared data-gathering practices on hate crime by member states' authorities.

In terms of hate speech per se, civil society organisations and universities are playing an important role in data gathering, especially as regards social media. Within the framework of the European project Positive Messengers, for example, bodies of seven different countries monitor hate speech against migrants and refugees. According to their report of late 2017, occurrence of hate speech increases in correlation with: increasing broadband access; increasing migration flows; electoral campaigns; national tragedies like terrorist attacks; and worsening economic conditions. Likewise, a study by the University of Warwick on Germany highlighted a correlation between occurrence of racism online and crimes against refugees.

Indeed, the web 2.0, social networks, and the “culture of comments” have led to an exponential increase in user-generated digital content as well as in opportunities for people to interact online. As a consequence, hate speech online has found much more ground for expression than in the past.

As explained by the UNESCO, this development is the poster child for technologies of potentially very positive impact posing their own challenges. The creation of the Internet had been accompanied by a utopian discourse that saw in virtual communication a great potential for emancipation and democratisation. Yet, as shown by a report by the Council of Europe, white supremacy groups in the US were quick to use the web to spread racist, xenophobic messages, including through the creation of “hate sites”. Also in Europe, many extremist groups rapidly developed a sophisticated online presence.

Since the 2000s, authorities have devoted increasing attention to hate speech on the Internet. In 2001, the Council of Europe adopted the Convention on cybercrime, the first multilateral treaty on the topic, followed in 2003 by the Additional protocol , a document promoting a number of measures to improve contrast to hate crime online.

Despite the lack of accurate data, there seems to be consensus on the fact that online hate is on the rise in terms of both occurrence and range of employed strategies. For instance, the 2015 report by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) , a body of the Council of Europe, cited the rise of hate speech online among the year's main trends. Another 2015 report by the Special rapporteur of the UN Human Rights Council for minority issues highlighted an “unprecedented growth” of hate speech online, while on "EU Internet Law " scholar Ioannis Iglezakis defined the Internet as the “new frontier” of hate speech.

Is hate speech a crime?

In European countries, the measures taken (or suggested) by institutions against hate speech are strongly influenced by international indications and recommendations. For example, the UN drafted a number of documents and recommendations on hate speech that states are invited to follow. As early as in 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prescribed that “any appeal to national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence must be forbidden by law”.

At the European level, the Council of Europe has been dealing with hate speech for decades, in terms of both legislative actions/recommendations and case law through the European Court of Human Rights . On the other hand, the interest of the European Union in the topic is much more recent, but very lively and on the rise . Given the EU's powers, especially in terms of digital market and shaping member states' policies, its initiatives can be very incisive. At the national level, virtually all European states have introduced norms to contrast at least some forms of hate speech.

In line with the recommendations by the UN and the Council of Europe, national and European authorities have regarded hate speech as a crime for a long time. This has made repression possible, even though under specific conditions, in proportioned ways, and following an assessment by the judiciary. However, since the 2000s, the use of criminal law has shown some limits, first of all in quantitative terms. As mentioned, the concept of hate speech has significantly expanded, and the very number of its occurrences on the Internet makes it hard for the judiciary to address them one by one.

On the other hand, the observation of the phenomenon and the case law have shown the limits and risks of relying on criminal law only: the risk that trials end up giving even more visibility to hate; the danger that authorities label legitimate dissent as “hate speech”; the possibility that broad definitions of hate speech leave too much room for discretionality by the judiciary and end up limiting freedom of expression.

The issue of assessing the relationship between freedom of expression and contrasting hate speech has been the object of many verdicts by the European Court of Human Rights. The Court mainly relies on the European Convention on Human Rights, that through article 10 protects freedom of expression, but through article 17 forbids to abuse the liberties acknowledged by the Convention to undermine its very foundations: basically, those who promote values in open contrast with the Convention cannot appeal to the freedom of expression granted by the Convention itself.

Referring to article 17, over the decades the European Court of Human Rights has rejected several appeals by individuals and actors that had been prosecuted for their statements. The case law shows that freedom of expression does not cover revisionist, pro-Nazi, or racist statements.

However, while some cases clearly fall under article 17, others require a more complex assessment of the rights at stake and of the measures taken by national authorities. In these cases, the Court carefully assesses the profile of the alleged criminal(s), their motivations, their objectives, the content and context of the statements, and the extent of their circulation.

Also when the Court acknowledges the legitimacy of measures that punish and remove expressions of hate, it still requires that restrictions have a precise juridical basis and that there are no alternatives available. Furthermore, restrictions must pursue legitimate objectives, like protecting the general interest and other people's rights. From the juridical point of view, the Strasbourg Court has also recognised the states' obligation to actively protect the victims of hate speech.

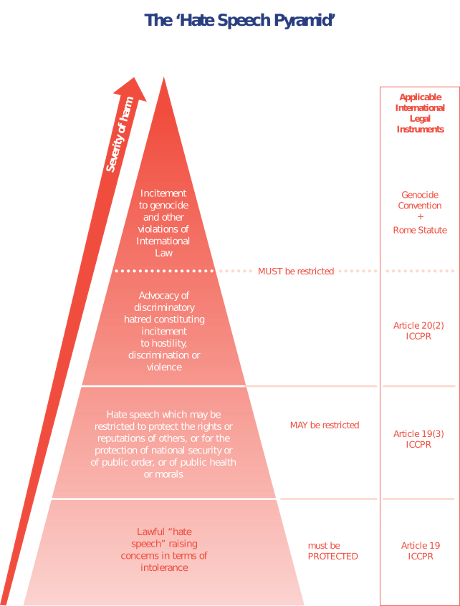

Against the many juridical and quantitative issues posed by regarding hate speech as a crime, recommendations by the UN and the Council of Europe invite states to criminalise “only serious and extreme forms of hate speech”, i.e. those that actively encourage violence and discrimination against a person or group. In all other cases, states are invited to explore alternative instruments to prevent or contrast hate speech.

Country case: Romania

In Romania, hate speech has not been systematically addressed so far. Several studies, including a report by ECRI published in June 2019, show that its main targets are Roma, Hungarian, Jewish, and LGBT persons, although hate speech against migrants has become more visible over the last few years. Despite some progress in the last five years, racist and intolerant hate speech in public discourse and on the internet has become a widespread problem, while the response of the criminal justice system to hate crimes is inadequate.

Politicians, mass media, and users of online media are equally active in producing hate speech. Yet, there are few statistics on hate crime and hate speech, also because there is no monitoring body. The National Council for Combating Discrimination (CNCD) is the country's main equality body and mostly deals with appeals. The National Audio-visual Council monitors audiovisual media, starting its own procedures and sanctioning discriminatory behaviours when necessary.

Since 2002, the CNCD has processed over 6,300 cases of discrimination, resulting in administrative sanctions or public recommendations. In 2006, the Council sanctioned the "New Right" group for publishing on its site xenofophobic and racist articles, ordering their removal. Hate speech is often used during electoral campaigns : the CNCD also sanctioned high-profile politicians, including former president Traian Basescu , for discriminatory statements against minorities.

As regards the legal framework and regulatory instruments , the 2014 criminal code contains some measures against hate speech. Romania transposed the dispositions of the European directive on audiovisual media , that forbids contents that incite hate. The media are held accountable for the contents they publish and brodcast, as well as responsible for moderating online comments. At present, however, very few norms apply to new media, IT companies, and Internet service providers.

How to contrast hate speech on the Internet?

When we talk about hate speech on the Internet, the main actors at play are online media and blogs, technological platforms, and other intermediaries such as search engines, providers, social networks, and so on. In particular, over the last few years, growing attention has been paid to the role of digital corporations in spreading hate speech, with increasing pressure for these subjects to put more effort into contrasting it on their platforms and stop regarding themselves as mere intermediaries. Also the European Commission asked for “more responsibility” and invited technological platforms to act more decisively and rapidly in preventing, identifying, and removing the illegal contents published by their users, threatening to resort to legislative measures .

An important issue involves the juridical responsibility of platforms for user-generated contents. In the case “Delfi vs. Estonia” (2015), regarding the responsibility for comments posted by users on the Estonian news portal “Delfi AS”, the European Court of Human Rights decided that the portal had “editorial control” over the comment section, so it should have prevented the publication of illegal comments, with a “proportioned” and “justified” limitation of freedom of expression. The verdict, that holds intermediaries accountable in contrast to what could be inferred from the Directive on electronic commerce (which, however, does not address the topic directly), generated an intense debate.

In some ways, contrasting hate speech online is more complicated than doing it elsewhere. As shown by the UNESCO, hate speech online is characterised by the anonymity of authors; the permanence of the contents; itineracy, i.e. the ability to spread through different platforms and environments; and the inter-jurisdictional and transnational character of the contents and platforms that host them.

While it is by now clear that private companies operating on the web are subject to the same norms and human rights standards that apply offline, identifying the juridical regime applicable in each case is not easy. If Internet service providers are subject to the laws of the country where they operate and search engines are subject to a multiple regime – that of the country where they are registered and those of the countries where they offer their services –, the situation is more complex for global social networks. In the absence of a supranational jurisdictional authority, and given the limited capacity of national jurisdictions, social networks tend to operate mainly according to their own terms of service.

Therefore, if hate speech online is not intrinsically different from hate speech offline, the nature of the online sphere poses specific challenges that make it difficult to identify responsibilities, develop adequate legal measures, and apply existing norms. This is why new approaches are needed that take into consideration the specificities of digital technologies.

In May 2016, the European Commission and four major social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Microsoft) adopted a code of conduct to contrast illegal hate speech online. Although these are not legally binding measures, companies commited to remove illegal hate contents within 24 hours from reporting, in line with national laws, and in particular with those transposing the EU's framework decision on racism and xenophobia and the directive on electronic commerce .

The application of the code of conduct is monitored and described in periodical reports by the European Commission. According to the latest report (February 2019), the companies have removed on average 71,7% of the contents reported by users and civil society organisations. Removals have constantly increased over in the period between May 2017 to December 2018. Nonetheless, there are differences between platforms: for example, Twitter is quite slow or reluctant to remove contents, following up on only 43,5% of reports (as of December 2018). Significant national differences also emerged: removal percentages range from Portugal's 38% to Cyprus's 100%.

The European Commission's choice to entrust private companies with such a significant role has been criticised under several aspects. This approach seems to foreshadow a privatisation of the fundamental rights regime, whereby large technological platforms act as law-makers, judges, and executors, bypassing supervision by the judiciary . As argued by the Centre for Democracy and Technology , a think-tank dealing with civil rights protection online, the absence of juridical supervision is very problematic , especially because hate speech issues require an open, transparent public debate.

According to critics, removing hate speech from the web does not equal removing it from society, but rather eliminates the possibility to contrast it with balanced, informed arguments (the so called counter-speech). Other critiques involve the scarce transparency of the algorhythms that filter contents reported to the platforms, the quality of moderators' work, and the excessive trust placed by the European Commission into technical instruments and the so-called “trusted flaggers”, certified users that commit to reporting illegal contents to platforms.

Another recurring critique involves the scarce transparency of the code of conduct. The code does not establish public databases on the work and decisions of the platforms, nor clear assessment criteria: should they apply their terms of service or European and national norms? As for the companies' role, the Council of Europe warned in a study from 2011: “companies are not immune from unjustified interferences. Their decisions sometimes stem from direct political pressure or politically motivated financial obligations, justified by compliance with terms of service”.

Country case: Germany

Germany is among the strictest European states in terms of removing hate speech online. In 2015, as the government decided to accept up to a million refugees and hate crimes increased, including several attacks against journalists as reported in this video, the country asked Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube to sign an agreement and commit to remove hate content within 24 hours from reporting, in compliance with national laws and in collaboration with organisations like Correct!v.

However, the German government later deemed actions by the major platforms insufficient and introduced the Network Enforcement Law (NetzDG). The ministry of Justice explained that the law was necessary because “verbal radicalisation is often the first step towards physical violence”. The new law entered into force on January 1, 2018, and prescribes sanctions up to 50 million Euros for social networks that fail to remove contents deemed illegal.

The law has been criticised by Green MPs like Renate Kuenast, who fear that the prospect of sanctions may lead to the removal of offensive, but not necessarily illegal contents. The German Federation of Journalists has drawn attention to the fact that “journalism's responsibility for contents cannot be delegated to platforms like Facebook, that may remove contents for commercial rather than editorial concerns”. Stressing the need to protect freedom of expression at all costs, EU Commissioner for the digital common market Andrus Ansip highlighted the need to improve media literacy and critical thinking to address hate speech.

Country case: France

The press law of 1881 defines freedom of expression and sanctions illegal hate speech. After the terrorist attacks of the last few years, the country saw a massive increase in hate speech, including by some politicians .

In 2015, the government launched a 2-year national plan against racism and anti-semitism , funded for 100 million Euros. In addition to strengthening sanctions against hate crime, the measure includes a plan against hate speech online , with the creation of a specific unit devoted to protecting Internet users from hate , starting from social platforms. The unit's tasks include monitoring the web and social platforms and facilitating hate speech reports by users.

According to French law, companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube enjoy the status of “guests” . Therefore, they are not responsible for what is published on their platforms, unless they have been warned. When an evidently illegal content is reported, the law requires them to inform the judiciary. In 2016, two civil society organisations found that the three social media platforms had removed only a minimum percentage (4% for Twitter; 7% for Youtube, and 34% for Facebook)of the 586 contents reported. The low reactivity of the platforms led in 2017 to an appeal by six anti-racist and anti-homophobic organisations . In July 2019, the French National Assembly approved a bill that would compel online giants like Facebook and Twitter to remove hate content within 24 hours . In the event of failure to respond within the established time frame or failure to offer users the means necessary to report similar content, the networks could face penalties involving a prison sentence and a fine between € 250,000 and € 1.25 million, depending on whether the 'propagator' of hatred is a natural or legal person. The new bill, compared to the German Network Enforcement Law (NetzDG), has been regarded as much stricter from the point of view of sanctions and has attracted criticisms and similar fears of "abusive censorship" by civil society, but not by opposition politicians. The bill must be approved by the Senate.

As regards the question of the boundaries between freedom of expression and hate speech , the French debate has developed around two main strands: first, the definition of the boundary that separates incitement to hatred from a crime of 'hate; secondly, the search for an educational or re-educational path that accompanies the removal of content deemed dangerous to overcome the 'feeling of censorship'. Moreover, after the attack on Charlie Hebdo, in France there was debate about how the boundaries of freedom of expression vary according to the subject of hate speech (the so-called 'double standard ').

How to prevent hate speech?

Many observers, including the UNESCO and the UN special rapporteur on minority issues , believe that legal measures are not sufficient to contrast hate speech. Social, cultural, and educational measures are needed to address the roots of the phenomenon, which is considered the symptom of a deeper problem.

According to the UNESCO, digital citizenship education is key to preventing hate speech online. It includes education to human rights and safe use of the Internet, promotion of information and media literacy, and development of critical skills. In the multitude of initiatives characterised by this approach, informing, analysing, and acting emerge as shared and complementary objectives.

As for information activities, we can mention the campaigns launched over the last few years to raise awareness on the phenomenon and its consequences as well as the collection and dissemination of information on hate speech and relevant norms. As regards the analysis of the phenomenon, it is crucial to identify hate speech , its roots, and its forms, in order to recognise and uncover them. In terms of actions, writing against hate speech, media monitoring, understanding hate speech dynamics, and counter-speech are among the most common options.

The initiative No Hate Speech , promoted by the Council of Europe and targeting youth, is an example of the complementary objectives of the educational approach. On the one hand, the movement promotes a campaign against hate speech in over 40 countries; on the other hand, it seeks to raise awareness on hate speech through a manual that addresses the issue in a human rights perspective. The movement also operates as a monitoring platform , so that users can report and discuss hate content online.

Youth is not the only target of educational initiatives against hate speech: many training instruments target law enforcement, the judiciary, teachers, and other civil society members. For example, the European project Prism develops transversal activities aimed at elaborating effective strategies and practices to foster better use of language, contrast hate speech, and promote a culture of respect.

For all these projects on preventing and contrasting hate speech, developing digital competences is crucial to uncover and combat hate speech online. This is clear from the wide range of digital formats used (videos, infographics, websites, blogs, social media), that make it possible to reach more people in transversal ways.

However, despite the wide comparative reasearch carried out over the last few years, for example within the project Positive Messenger , there is no exhaustive assessment of the results of educational and cultural answers to hate speech, and their actual impact is not clear. It seems, however, fair to say that alternatives to legal measures are necessary.

What is the role of journalists?

If the role of social networks in spreading hate has been extensively discussed, traditional media have gathered less attention . As early as in 1978, the UNESCO stressed the responsibilities of mass media in the fight against racism, highlighting their role in “voicing the concerns of oppressed populations [...] informing on the objectives, aspirations, cultures, and needs of all peoples [...] with no distinction of race, sex, language, religion, or nationality”. Two decades later, referring to the Yugoslav dissolution wars, the Council of Europe stressed the media's responsibility in opposing violence and hate speech.

Media monitoring in several national contexts has highlighted how media often voice hate speech, although not always consciously. This is particularly true during electoral campaigns because of the phenomenon of newsworthiness of hate , i.e. the viral circulation of polemics and provocations: the media that choose to cover them contribute to disseminate hate speech. This highlights the importance of trainings that raise journalists' awareness on how to report news without falling into hate speech and to disseminate good practices.

This aspect is central to the journalistic profession, as confirmed by the fact that contrast to hate speech is covered in many professional codes of conduct – 120, according to the database “Accountable journalism ” (the largest collection of press organisations' ethical codes worldwide).

In turn, the Ethical Journalism Network – that seeks to help journalists all over the world address the ethical dilemmas posed by the so-called post-truth era – has recently published a test to warn journalists about unwittingly using and spreading hate speech. Before reporting a statement, the test suggest assessing the author and target of the message, its goals and content, and the context of circulation.

These questions lay the ground for further discussion of what constitutes news: even with the best of intentions, the choice not to give visibility to hate content may end up “censoring” a phenomenon that can only be contrasted if people are aware of it. Should a journalist committed to effectively contrasting hate speech avoid spreading it, or rather expose and criticise those who use it?

Once again, doubts and questions abound, and univocal answers seem hard to find. Certainly there is an old problem (hate between human beings) and there are new ways to express it (e.g. social networks). However, there are also citizens, institutions, and transnational organisations engaged in a democratic debate and committed to seeking effective solutions.

Tags: Hate speech Freedom of expression EU Member States

This content is part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries. The project is co-funded by the European Commission.