A special dossier curated by Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa for the Resource Centre on Press and Media Freedom

Last January 1st, Bulgaria took over the 6-month Presidency of the Council of the European Union for the first time. After a troubled transition from Communism, in its first decade as a member of the EU (2007-2017) the country registered significant changes. As structural funds – which reached almost 6 billions Euro in 2018, over 9% of the GDP – visibly impacted on infrastructure, Bulgaria has found in the EU a solid shelter from the economic crisis that started in 2008 and a new geopolitical identity that can inform its future.

If financial indicators improve, the same cannot be said for the state of democracy. The condition of press freedom is among the most concerning signs. Despite the constitutional and legislative guarantees, media pluralism and independence have suffered significant restrictions over the last ten years: in the annual rankings by Reporters Without Borders, the country dropped from 35th in 2006 to 109th in 2017 . How can we explain such a downfall? What is going on in the country?

In order to provide an up-to-date outlook on the state of freedom of expression in Bulgaria, this dossier draws on the materials available in the Resource Centre curated by Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT).

Privatisations: between foreign capitals and local oligarchs

In the nineties, when Bulgaria liberalised the information market, press, TV, and radio outlets were purchased by private actors. Foreign media groups showed up to invest in an emerging economy. Among them was German WAZ , that in 1997 bought then major dailies “24 Chasa” and “Trud” – in 2010, when it left the scene, pluralism in the country started to decline. As denounced by journalist Stefan Antonov in the study “The age of the oligarchs”, the outbreak of the economic crisis in 2008-2009 allowed few powerful businessmen to take over politics and, consequently, information. The drop in advertising revenues has made media more dependent on state funding and, as a consequence, more vulnerable. According to the latest report by IREX, media in Bulgaria can currently be divided into 4 categories: public broadcasters (BNT, BNR and BTA); outlets owned – directly or indirectly – by “oligarchs”; international media groups, mostly on their way out (bTV and Nova TV); and media struggling to remain independent.

While there are no barriers for the press, radio-TV stations need a licence from the Council of Electronic Media (CEM), a theoretically independent body with a budget approved by Parliament. Several international organisations and studies have criticised the arbitrariness of the issuing of licences by CEM and the virtual lack of audience measurement. It is equally hard to determine which newspapers are the most read in Bulgaria, as the National Bureau of Statistics does not register sales, but only the distribution of copies. In the last available year, 2016, 262 active newspapers and magazines were registered (there were over 900 in 2007), for a total of 229,000 copies in circulation. If considering that one of the country's main media group, the New Bulgarian Media Group, is also the main stakeholder (80%) of the only press distribution company, we may conclude that the lack of actual measurements could stem from a conflict of interests.

An insufficient legal framework

Press freedom is granted by the 1991 Constitution . Namely, article 40 (1) establishes that the press must be free and not subject to censorship. In Bulgaria, press outlets are regarded as “free commercial entities” and there are no specific laws regulating their activity. On the other hand, the activity of audio-visual media is regulated by the 1998 Law on radio and television , which in 2010 was harmonised with the Directive on audio-visual services (2007).

The existing laws against political interference in the media do not explicitly forbid politicians to own outlets or direct/indirect monitoring mechanisms. At the same time, Bulgarian legislation does not adequately protect independent editorial policies. Article 11 (2) of the aforementioned law reads: “Journalists and artists that have signed a contract with providers of media services shall not receive instructions by persons and/or groups outside the management bodies of the multimedia service providers”. Boundaries remain undefined in terms of the relationship between owners, editors, and journalists, while article 6 (5/6) of the same law establishes that such dispositions do not apply to electronic versions of newspapers and magazines.

Several laws deal with transparency of media ownership – a crucial topic that intersects with the issue of political interference. Since 2010, the “Law on compulsory deposition of press and other works” prescribes that press and electronic media submit to the Ministry of Culture a statement with the names of the owners. In July 2014, another law entered into force that forbids offshore companies to own TV or radio licenses. However, several observers highlight the lack or partial implementation of the laws.

According to Bulgarian law, media concentration is regulated by competition law. In an interview with OBCT , jurist Nelly Ognyanova stated: “The media law lays down only a general principle that a media licensing application must not be in violation of the competition protection legislation. Unfortunately, this general provision in the Law on Radio and Television has proven inadequate”. According to Ognyanova, if there were the political will, the media could operate in an adequate legal framework: “In brief, the development of free and democratic media in this country is also a function of the Bulgarian Parliament's drive for democracy”.

In February 2015, after visiting the country, the Council of Europe (CoE) Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks published a report detailing the need to introduce laws on transparency of ownership structures and sources of funding. The same study also criticises the definition of defamation and slander in media laws: although detention for defamation was abolished in 1999, for slander (146 C.C.), criminal defamation (147 C.C.) and public slander (148 C.C.) there are sanctions up to 10,000 Euros – measures that, although rarely applied, according to the CoE contribute to strengthening an already endemic “self-censorship culture”.

Finally, in 2000 Bulgaria approved the law on access to information , that seeks to protect sources as a crucial part of investigative journalism. However, considering the obstacles met by both journalists and citizens in accessing documents regarding the state, also in this case the law does not appear to be implemented in a consistent manner.

Media “without owners”

Several international studies agree that concentration of ownership and lack of transparency are among the main obstacles to press freedom in Bulgaria.

Currently, there are two public registers: CEM for radio-TV stations and the Ministry of Culture for press. However, this system does not ensure transparency, as most outlets are registered under offshore companies, anonymous companies, or proxies. On the other hand, even when owners are recognisable, their interests and sources of funding are not always clear; for example, several journalists declared to be in the dark about the “true owners” and editorial policy of their outlet. According to this report by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS), there are several reasons to doubt that some companies or individuals registered as owners are the actual decision-makers. Firstly, as Bulgarian media are generally operating at a loss and it is not clear where they obtain funds to balance their budget. Journalism's independence is weakened by the increasing dependence on banks and other external actors – for example the links between a part of the most influential media with the now failed Corporate Commercial Bank. Media, politics, and finance are therefore intertwined in a constant process of mediating resources and information.

In terms of formal ownership structures, the Bulgarian media market has undergone significant changes over the last 10 years. In 2007, Irena Krusteva (mother of controversial politician Delyan Peevski) purchased dailies “Monitor”, “Telegraph”, and “Politika” and founded the New Bulgarian Media Group, which currently owns 6 newspapers and holds the monopoly of distribution. Over the decade of European integration, the main tendency was the withdrawal of prestigious international companies, often replaced by offshore holdings. Among the latest sales is that of Nova Broadcasting, one of the country's main media groups, with 7 TV channels and 19 websites, which transferred from the Swedish Modern Times Group to Czech tycoon Peter Kellner, one of the richest men in Central-Eastern Europe.

As for media baron and MP Delyan Peevski, repeatedly cited by all international studies as the poster child for conflicts of interest, his dominant position does not translate so much into self-promotion as into serving the interests of the government – even when Peevski's Turkish minority party is in the opposition. Last February, Peevski himself presented a law proposal on transparency that would oblige media outlets to declare their external sources of funding other than advertising. In a letter published by some Bulgarian newspapers, Peevski wrote that such initiative seeks to “stop speculations by some media” on the allegedly unclear ownership of media in Bulgaria. According to lawyer Alexander Kashumov “There is not even an attempt to hide the fact that this law targets those media that are in competition [with Peevski],”: first of all the Economedia Group that depends on the funding by the America for Bulgaria Foundation. Referring to Peevski's legislative initiative, jurist Nikoleta Daskalova commented: “I think the purpose of this draft legislation is not in its adoption, but in its very proposal. It seeks to show that, ‘We are clean and we are showing that by asking for transparency’, legitimizing the people who drafted it”.

In the aforementioned report by the CoE, the Commissioner Nils Muiznieks talked about a “war” between the largest private groups operating in the information sector – a polarisation that, in his view, reflects the country's political and economic divisions: on the one hand, Peevski's "army"; on the other hand, the “battalion” revolving the Publishers' Union of Sasho Donchev (owner of Sega), Ivo Prokopiev, and Theodore Zahov (owners of Economedia Group). The distance between the two sides is illustrated by the existence of two separate “ethic codes”: the latest was written in 2014 by the journalists of the New Bulgarian Media Group, only to question the validity of the first, adopted in 2004. Sometimes, this latent contrast becomes explicit through stances taken by journalists in defence of their group. For example, Lyubomira Budakova and and Natalia Radoslavova, journalists working for the New Bulgarian Media Group, recently denounced the existence of a “fake news factory” against Peevski's media. However, this polarisation seems to affect mainly the outlets that try to exist outside of it. Examples include the denigration campaign started by Peevski's newspapers against investigative journalism website “Bivol”. Launched in 2015, the campaign followed – not by coincidence – the publication of some articles on offshore companies and abuse of EU funds.

The many faces of censorship: political influence and intimidation

“Your words could get you fired”, said Bulgarian vice-premier Valeri Simeonov toTV host Victor Nikolaev, who had asked too many inconvenient questions during a show broadcast last October on private station Nova TV. This episode, which led to hundreds of citizens to protesting, illustrates the current state of information in Bulgaria. Over the past few years, the economic crisis has reduced sales and advertising, making all media – public, private, TV, radio or press – more and more dependent on state support. Not unintentionally, the European Association of Bulgarian Journalists (AEJ - Bulgaria) titled its last report “The big comeback of political pressure”.

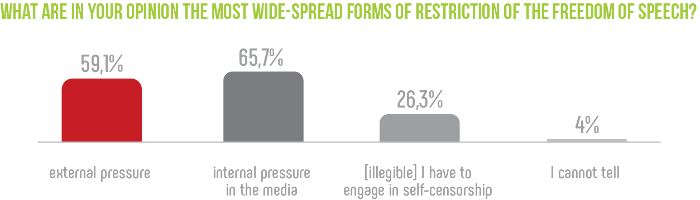

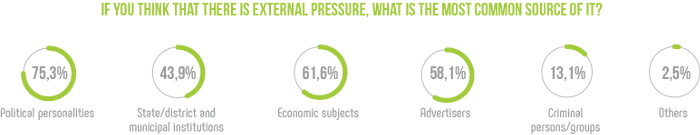

Over 2/3 of the 200 Bulgarian journalists interviewed by the Association admit that most of the interference comes from politicians, and 92% define interferences as “common” and “widespread”. Dailies, both national and regional, are the most affected. The most common forms of restriction on freedom of expression are identified as “internal” (65,7%) and “external” (59,1%) pressures, followed by “self-censorship” (26,3%), while just a tiny minority is not able to answer (4%). These figures are directly connected to government control on distribution of public resources and economic support to publishers. The Media Freedom White Paper published in 2018 by the Union of Publishers in Bulgaria (UBP) states that the government's financial support plays “a more and more crucial role” in the media landscape.

In its latest report the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CPMF) found a high risk of political interference in the information sector. What raises particular concern is the fact that the resources selectively allocated by the state mostly derive from the EU structural funds for communication. According to Reporters Without Borders (RWB), “the government allocates EU funds to some media in complete lack of transparency, virtually corrupting publishers so that they will be careful when reporting politics or abstain from dealing with problematic news altogether”. Addressing corruption in the country, a recent study commissioned by the Green group in the European Parliament highlights the same problem, stating that “some media, that are believed to have violated journalism's deontological standards, benefit from the EU funds they receive to promote EU programmes”.

According to data by SEEMO, between 2007 and 2014 over 36 million Euros were spent to inform the public about the results of the community Rural Development Programme. The funds were mostly allocated to 5 TV stations (bTV, BNT, Nova TV, TV Europe, Channel 3) and 3 radio stations (Radio Focus, Bulgaria On Air, BNR).

"This money is distributed to the media by Ministries to inform on the implementation of EU policies in Bulgaria, however details are not available on the allocation process: we do not know which outlets receive the money, according to which criteria, and how”.

(Maria Neikova, lecturer at the Faculty of Journalism of the University of Sofia St. Kliment Ohridski)

In 2013, former Minister of Agriculture Miroslav Naydenov was intercepted while confiding to current premier Boyko Borisov and General Attorney of Sofia Nickolay Kokinov that, to receive those funds, media outlets had to agree to “unwritten conditions”. The vulnerability of newsrooms increases with the distance from the capital, as working conditions deteriorate (80% of local journalists interviewed by AEJ declare a salary below 500 Euros per month). An article by journalist Spas Spasov for “Dnevnik” and “Kapital” showed that, between 2013 and 2015, Bulgarian municipalities spent at least 1.5 million Euros to fund local newspapers, TV stations, and radio stations, securing their support through their own or EU funds.

Frequent intimidations, increasing violence

Publishing reports or criticising politicians can have direct consequences on individual journalists as well. For example, “Bivol” reporter Dimitar Stoyanov sought refuge in the programme “Journalist in Residence” of the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF ) after receiving threats for publishing a report on corruption in the public service. In April 2016, one of Bulgaria's main commercial channels, Nova TV (then owned by Swedish group Modern Times), ended the contract of cartoonist Chavdar Nikolov after he had drawn premier Bojko Borisov as the leader of a group of “migrant hunters” on the border between Bulgaria and Turkey. The channel, that also deleted all of Nikolov's cartoons from its website, defined the timing of Nikolov's dismissal as “a coincidence”.

Overall, crimes against journalists in Bulgaria are rare, but are growing – mainly because of the inefficiency of the judiciary: impunity, perceived as the norm, fosters self-censorship in journalists and protects criminals. As there is no specific legislation that protects journalists, attacks to the press are monitored by local or international NGOs. A blatant example is the case of Georgi Ezekiev, publisher of online outlet “Zov News”, that at the end of November 2017 learnt from an informer that the mafia organisation his newspaper was investigating on was planning his murder. Although the threats are recorded in a video interview , so far [April 2018] the police has not opened an investigation.

Although no journalist has been killed since 2010, there have been serious attacks: for example Stoyan Tonchev, editor of local news portal “Pomorie” and local politician, was attacked and beaten violently with a baseball bat in early 2016. In 2012 the car of Lidia Pavlova , a journalist specialising in organised crime in south-east Bulgaria, was set on fire, and the same happened to Genka Shikerova, bTV investigative journalist, in 2013 and 2014, and reporter Zornitsa Akmanova in October 2017. According to journalist Maria Dimitrova “aggressions are more common than lawsuits against journalists. In Bulgaria people tend not to resort to legal procedures to solve disputes. However, rather than physical threats reporters receive intimidation calls, insults, or the like”. In 2017, at least 10 cases of intimidation were registered by AEJ and Index on Censorship.

Bulgarian citizens, European citizens

Unlike in the economic sphere, EU membership does not seem to have had a positive impact on the Bulgarian media landscape. What is not clear is the degree of awareness of Bulgarian citizens of the constraints on freedom of speech and expression.

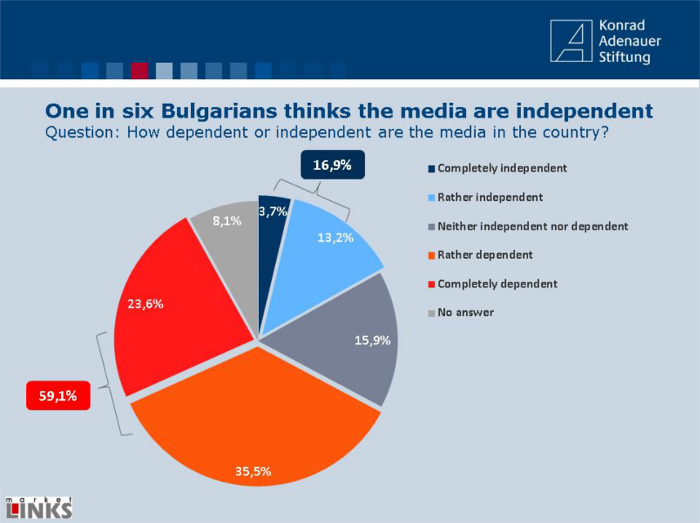

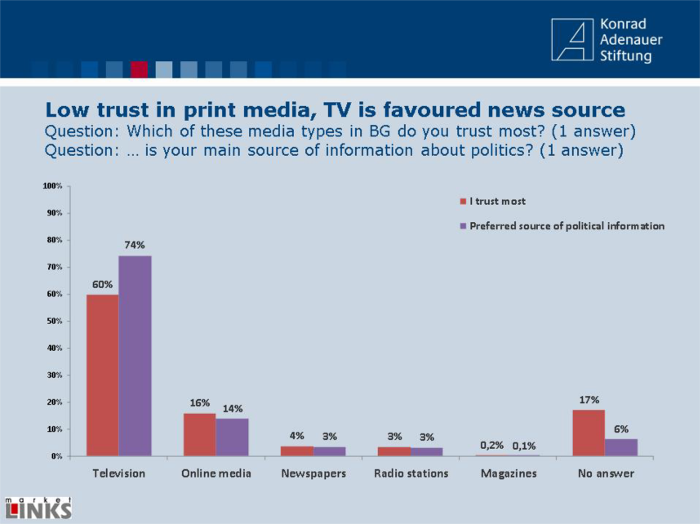

According to a study on “media literacy” by Open Society – Sofia, poor education and distrust in state institutions weaken the “immune system” of Bulgarian citizens against fake and instrumental news, also supporting the spread and appeal of conspiracy theories. On the other hand, according to a survey carried out in 2015 by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 59% of the legally adult population regards national media as “non independent”. The most trusted media remains by far television (60%), followed by the Internet (16%), newspapers (4%), and radio (3%). Yet, if 74% of respondents look to TV for political news, 63% specify they are not satisfied with the level of information. In 2014, European civil society organisations gathered around European Alternatives promoted a European Citizens' Initiative to ask the European Commission for a legislative initiative protecting free and plural information. The campaign collected “only” 204,812 signatures (the Lisbon Treaty requires at least one million); despite it ultimately not being the successful, promoters highlighted how Bulgaria, a “country symbol of deteriorating freedom of expression”, was among the first member states contributing to the campaign .

In a recent interview with OBCT, Lada Trifonova Price, journalism lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University and director of education a the Centre for Freedom of the Media , stated that the only way to bring substantial change in Bulgaria – a country she sees as “totally devoid of respect for the journalistic profession” – would be for the EU to develop a much more robust mechanisms to enforce its Charter of Fundamental Rights, especially Article 11 on freedom of expression. Similarly, third-sector organisations and journalists which have been denouncing for years the practice of “state advertising”, have asked Brussels to demand the establishment in Bulgaria of an independent body to monitor public funding to the information sector. In this regard, journalist Atanas Tchobanov, editor of investigative portal Bivol.bg , a href="h

Tags: Bulgaria Freedom of expression Media freedom Media ownership Media pluralism Censorship European Court of Human Rights European policies and legislation EU Member States

This content is part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries. The project is co-funded by the European Commission.